RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

When the respiratory system is mentioned, people generally think of breathing, but breathing is only one of the activities of the respiratory system. The body cells need a continuous supply of oxygen for the metabolic processes that are necessary to maintain life. The respiratory system works with the circulatory system to provide this oxygen and to remove the waste products of metabolism. It also helps to regulate pH of the blood.

Respiration is the sequence of events that results in the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the atmosphere and the body cells. Every 3 to 5 seconds, nerve impulses stimulate the breathing process, or ventilation, which moves air through a series of passages into and out of the lungs. After this, there is an exchange of gases between the lungs and the blood. This is called external respiration. The blood transports the gases to and from the tissue cells. The exchange of gases between the blood and tissue cells is internal respiration. Finally, the cells utilize the oxygen for their specific activities. This is cellular metabolism, or cellular respiration. Together these activities constitute respiration.

Ventilation, or breathing is the movement of air through the conducting passages between the atmosphere and the lungs. The air moves through the passages because of pressure gradients that are produced by contraction of the diaphragm and thoracic muscles.

Pulmonary ventilation

Pulmonary ventilation is commonly referred to as breathing. It is the process of air flowing into the lungs during inspiration (inhalation) and out of the lungs during expiration (exhalation). Air flows because of pressure differences between the atmosphere and the gases inside the lungs.

Air, like other gases, flows from a region with higher pressure to a region with lower pressure. Muscular breathing movements and recoil of elastic tissues create the changes in pressure that result in ventilation. Pulmonary ventilation involves three different pressures:

- Atmospheric pressure

- Intraalveolar (intrapulmonary) pressure

- Intrapleural pressure

Atmospheric pressure is the pressure of the air outside the body.

Intraalveolar pressure is the pressure inside the alveoli of the lungs.

Intrapleural pressure is the pressure within the pleural cavity.

These three pressures are responsible for pulmonary ventilation.

- Inspiration

Inspiration (inhalation) is the process of taking air into the lungs. It is the active phase of ventilation because it is the result of muscle contraction. During inspiration, the diaphragm contracts and the thoracic cavity increases in volume. This decreases the intraalveolar pressure so that air flows into the lungs. Inspiration draws air into the lungs. - Expiration

Expiration (exhalation) is the process of letting air out of the lungs during the breathing cycle. During expiration, the relaxation of the diaphragm and elastic recoil of tissue decreases the thoracic volume and increases the intraalveolar pressure. Expiration pushes air out of the lungs.Under normal conditions, the average adult takes 12 to 15 breaths a minute. A breath is one complete respiratory cycle that consists of one inspiration and one expiration.

An instrument called a spirometer is used to measure the volume of air that moves into and out of the lungs, and the process of taking the measurements is called spirometry. Respiratory (pulmonary) volumes are an important aspect of pulmonary function testing because they can provide information about the physical condition of the lungs.

- Respiratory capacity (pulmonary capacity) is the sum of two or more volumes.

Factors such as age, sex, body build, and physical conditioning have an influence on lung volumes and capacities. Lungs usually reach their maximumin capacity in early adulthood and decline with age after that.

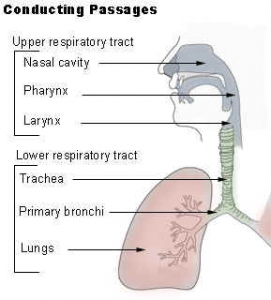

Conducting Passages

The respiratory conducting passages are divided into the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract. The upper respiratory tract includes the nose, pharynx, and larynx. The lower respiratory tract consists of the trachea, bronchial tree, and lungs. These tracts open to the outside and are lined with mucous membranes. In some regions, the membrane has hairs that help filter the air. Other regions may have cilia to propel mucus.

- Nose and Nasal Cavities

- Pharynx

- Larynx & Trachea

- Bronchi, Bronchial Tree, and Lungs

Nose and Nasal Cavities

The framework of the nose consists of bone and cartilage. Two small nasal bones and extensions of the maxillae form the bridge of the nose, which is the bony portion. The remainder of the framework is cartilage and is the flexible portion. Connective tissue and skin cover the framework.

Pharynx

Pharynx

The pharynx, commonly called the throat, is a passageway that extends from the base of the skull to the level of the sixth cervical vertebra. It serves both the respiratory and digestive systems by receiving air from the nasal cavity and air, food, and water from the oral cavity. Inferiorly, it opens into the larynx and esophagus. The pharynx is divided into three regions according to location: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx (hypopharynx).

The nasopharynx is the portion of the pharynx that is posterior to the nasal cavity and extends inferiorly to the uvula. The oropharynx is the portion of the pharynx that is posterior to the oral cavity. The most inferior portion of the pharynx is the laryngopharynx that extends from the hyoid bone down to the lower margin of the larynx.

The upper part of the pharynx (throat) lets only air pass through. Lower parts permit air, foods, and fluids to pass.

The pharyngeal, palatine, and lingual tonsils are located in the pharynx. They are also called

Waldereyer’s Ring.

Layrynx

The larynx, commonly called the voice box or glottis, is the passageway for air between the pharynx above and the trachea below. It extends from the fourth to the sixth vertebral levels. The larynx is often divided into three sections: sublarynx, larynx, and supralarynx. It is formed by nine cartilages that are connected to each other by muscles and ligaments.

Bronchi, Bronchial Tree, and Lungs

Bronchi and Bronchial Tree

In the mediastinum, at the level of the fifth thoracic vertebra, the trachea divides into the right and left primary bronchi. The bronchi branch into smaller and smaller passageways until they terminate in tiny air sacs called alveoli.

The cartilage and mucous membrane of the primary bronchi are similar to that in the trachea. As the branching continues through the bronchial tree, the amount of hyaline cartilage in the walls decreases until it is absent in the smallest bronchioles. As the cartilage decreases, the amount of smooth muscle increases. The mucous membrane also undergoes a transition from ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium to simple cuboidal epithelium to simple squamous epithelium.

The alveolar ducts and alveoli consist primarily of simple squamous epithelium, which permits rapid diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Exchange of gases between the air in the lungs and the blood in the capillaries occurs across the walls of the alveolar ducts and alveoli.

Lungs

The two lungs, which contain all the components of the bronchial tree beyond the primary bronchi, occupy most of the space in the thoracic cavity. The lungs are soft and spongy because they are mostly air spaces surrounded by the alveolar cells and elastic connective tissue. They are separated from each other by the mediastinum, which contains the heart. The only point of attachment for each lung is at the hilum, or root, on the medial side. This is where the bronchi, blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves enter the lungs.

The right lung is shorter, broader, and has a greater volume than the left lung. It is divided into three lobes and each lobe is supplied by one of the secondary bronchi. The left lung is longer and narrower than the right lung. It has an indentation, called the cardiac notch, on its medial surface for the apex of the heart. The left lung has two lobes.

Each lung is enclosed by a double-layered serous membrane, called the pleura. The visceral pleura are firmly attached to the surface of the lung. At the hilum, the visceral pleura is continuous with the parietal pleura that lines the wall of the thorax. The small space between the visceral and parietal pleurae is the pleural cavity. It contains a thin film of serous fluid that is produced by the pleura. The fluid acts as a lubricant to reduce friction as the two layers slide against each other, and it helps to hold the two layers together as the lungs inflate and deflate.

PATHOLOGICAL CONDITIONS

Croup: Acute respiratory syndrome in children and infants characterized by obstruction of the larynx barking cough and strider.

Diphtheria: Acute infection of throat and upper respiration tract caused by chorine bacterium diphtheriae. It forms a leathery opaque membrane in the pharynx or in the respiratory tract causing an obstruction in the airflow, which may lead to health.

Pertusis: A bacterial infection of pharynx, larynx and trachea caused by bardetella pertusis, a highly contagious bacterium with woofing cough.

Asthma: Spasm and narrowing of the bronchus leading to bronchial airway obstruction caused by an allergen, gives paroxysmal (sudden) dyspnea, wheezing, and cough.

Chronic bronchitis: inflammation of the bronchi persisting from a long time due to infection or cigarette smoking leading to accumulation of mucus in bronchioles and COPD.

Atelectiasis: an incomplete expansion of the alveoli causing collapsed airless functionless lungs.

Emphysema: Hyper inflation of air sacs with destruction of alveolar walls causing loss of elasticity and breakdown of alveolar walls result in loss of air movement in air sac.

Pneumonia: Acute inflammation & infection of alveoli filling with pus in the lungs.

Pulmonary edema: Swelling and fluid collection in the air sacs and in the bronchioles in cases of congestive heart failure.

Pulmonary embolism: It is a process of obstruction of blood vessel by emboli like fats, clots, air, a chemical, leading to death of the pulmonary tissue called as pulmonary infraction.

ALLERGIC RHINITIS

Allergic rhinitis may be defined as the inflammation of nasal mucosa brought about by airborne pollens that react to release histamine. In other words, when some people breathe pollens that are in the air, the pollens cause histamine to be released. The excess of histamine in the body causes nasal mucosa to become inflamed. Causes of allergic rhinitis, more common during the warmest months of the year, include hay fever and allergic disorders which are common during seasons when the pollen count is high. Allergic rhinitis is also caused by house dust, occupational dust, molds, and animal dander (feathers, wool in blankets). Certain foods and drugs cause allergic rhinitis symptoms; sometimes bacteria cause this problem. The symptoms include:

- Nasal congestion.

- Profuse watery discharge.

- Itching of nose and conjunctiva.

- Sneezing.

PARANASAL SINUSITIS

Paranasal sinusitis is an infection of the mucous membranes that line the paranasal sinuses. Since the membrane that lines these sinuses is continuous with that of the of the nose and throat, paranasal sinusitis is a common complication of any upper respiratory infection. Causes of paranasal sinusitis include viruses, streptococci, and pneumococci.

Signs and symptoms of acute paranasal sinusitis are like those of acute rhinitis but are more severe. Included are headache, worse during the day; facial and tooth pain; tenderness over the sinuses; and fever and chills. There may be chronic recurrences of these signs and symptoms along with postnasal drip.

COMMON COLD

The common cold is a contagious, viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. The cold is usually caused by a strain of rhinovirus. Over ninety distinct strains of rhinovirus are known to cause the common cold. Although not everyone is susceptible to infection from a cold virus, this respiratory infection occurs more often than all other diseases combined. Whether or not a person develops a cold after being exposed to a cold virus is determined to some extent by the person’s general health. Fatigue, chilling of the body, wearing wet clothes and shoes, and the presence of irritating substances in the air make it more likely that the person will develop a cold.

These are signs and symptoms of the common cold:

- Malaise (general feeling of being unwell).

- Fever/chills.

- Headache.

- Nasal discomfort.

- Dry, sore throat.

- Cough (either productive or nonproductive).

- Mild leukocytosis (temporary increase in number of leukocytes in the blood).

ACUTE PHARYNGITIS

Acute pharyngitis is an inflammation of the pharynx. This disease, inflammation of the mucosa of the pharynx, usually occurs as part of an upper respiratory tract disorder. The nose, sinuses, larynx, and trachea may also be affected. The most common causes are bacterial or viral infection. Very rarely, acute pharyngitis is caused by inhalation of irritant gases or ingestion of irritant liquids. Sometimes, acute pharyngitis is one symptom of a specific disease such as measles, chickenpox, scarlet fever, or whooping cough.

Common signs and symptoms are listed below. A complication may be a secondary infection.

- Dry and sore throat.

- Fever.

- Malaise.

- Strep infection may be present with white pus pocket formation.

- Cough.

ACUTE TONSILLITIS/STREP THROAT

Tonsillitis: Tonsillitis is a painful disease caused by bacteria or viruses that infect one or both of the palatine tonsils. People between the ages of ten and forty have the majority of tonsillitis attacks.

Strep throat: Strep throat is an infectious disease that affects the membranes of the throat and tonsils. This disease is also called septic sore throat, acute streptococcal pharyngitis, and acute streptococcal tonsillitis. The disease is caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococci bacteria. It spreads from person to person through droplets of moisture sprayed from the nose and mouth. Some people only carry the bacteria. These carriers exhibit no symptoms themselves but spread the disease.

Signs/Symptoms include:

- Sore throat.

- Strong breath odor.

- Pain in swallowing.

- Fever/chills.

- Posterior cervical lymphadenopathy (disease of the lymph nodes).

- Headache.

- Malaise.

- Red or swollen tonsils or pharynx (with or without fluid, cells, or cellular debris from blood vessels (exudates)).

- Increased white blood cells with bacterial pharyngitis.

- With bacterial pharyngitis (strep throat), the throat culture is positive.

ACUTE BRONCHITIS

Acute bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchial mucous membrane of the bronchial tree. Infection, dust, chemical agents, and/or allergies can cause bronchitis. When the bronchi are infected, the mucous membranes (linings) of the bronchi secrete mucus and pus cells (white blood cells that can attack infectious agents). The large outpouring of mucus partially obstructs the airways. Additionally, the irritated membranes may swell, further obstructing the airways.

Signs/Symptoms include:

- Chilliness.

- Malaise.

- Soreness and constriction behind the sternum-worse when patient coughs.

- Slight fever.

- Cough, at first dry and painful; later, green or yellowish sputum with pus cells.

PLEURITIS

Pleuritis is an inflammation of the pleural lining, a lining that covers the lungs and the chest cavity. The two surfaces of this lining are moist and allow the lungs to move smoothly over the chest wall when a person breathes. The surfaces of the lining become dry and rough and rub together when the pleura lining is inflamed. This condition, called pleurisy or pleuritis, is very painful and becomes more painful when the person breathes deeply or coughs. Most cases of pleuritis occur as complications of some other respiratory condition such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, or another infectious disease. The underlying disease must be treated in order to cure the pleuritis.

Signs/Symptoms: Pleuritis signs and symptoms include the following:

- Pain–varies from vague discomfort to sharp severe stabbing in the chest. The pain becomes worse when the person coughs or breathes deeply.

- Respirations–short, shallow, and rapid. Motion–limited on the affected side.

- Breath–diminished sound.

- Fever.

- Chills.

- Friction rub–usually heard only after 24 to 48 hours.

PNEUMONIA

Pneumonia is an acute infection of the alveoli spaces of the lungs. Causes of pneumonia include injury to the respiratory mucosa with pneumonia as a secondary infection, influenza, common colds, and bronchitis.

There are three types of pneumonia: bacterial; mycoplasmal (bacteria having no cell wall and bounded by a triple-layered membrane); viral. Bacterial pneumonia is further subdivided into these types: pneumococcal; staphylococcal; klebsiella (Friedlander’s bacillus); streptococcal; and influenza bacillus.

Signs/Symptoms include:

- Mild nasopharyngitis (inflammation of the nasopharynx)– several days before onset of the disease.

- Sudden onset of illness.

- Vomiting.

- Severe chest pain–in 70 percent of the cases.

- Productive cough–rusty sputum.

- Fever (103 – 106oF)/chills.

- Often acutely ill.

- Dyspnea (labored breathing) and cyanosis. Cyanosis in light-skinned individuals gives a bluish cast to skin, lips, and nail beds. In dark-skinned individuals or blacks, the discoloration is grey or grayish. The cause is not enough oxygen in the blood.

- Decreased movement on one side of the chest.

- Severe, shaking chill.

- Signs of consolidation (inflammatory solidification of the lung); dull to percussion; bronchial breath sounds; fine rales.

Hyperventilation:

Hyperventilation, a common response to phsychological stress, is a condition that develops as a result of an individual breathing too deeply and too rapidly. Blood pH (hydrogen ion) is raised above normal, and the body experiences alkalosis (a condition in which the blood pH is between 7.45 and 8.00). By breathing as rapidly as possible for three to five minutes, a person can bring on the signs and symptoms of hyperventilation deliberately.

Hyperventilation Syndrome:

Patients who are anxious and often feel fatigue, nervousness, and dizziness may suffer from hyperventilation syndrome. The individual may breathe rapidly, breathing out so much carbon dioxide that he becomes unconscious. Unconscious, he begins to breath normally again, the carbon dioxide level becomes normal, and he regains consciousness. When the patient becomes nervous and anxious again, he is likely to experience hyperventilation syndrome again.

The following signs/symptoms are characteristic of a hyperventilation syndrome attack:

- Nervousness.

- Tachypnea–rate of breathing is excessively high (for adults over 25 respirations/per minute).

- “Unable to catch breath.”

- Dizziness.

- Tingling or numbness around mouth or in hands and feet.

- Carpopedal spasm–spasm of muscles in the carpus (the joint between the hand and the wrist and/or spasm of muscles in the foot).

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is a chronic disease caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The initial disease may not be noticed, but eventually the infection may spread to various parts of the body–tuberculosis of the bones and joints; intestinal tuberculosis; urinary tract tuberculosis. The incidence of tuberculosis is less today than in the past. In the United States Army in World War II, the number of tuberculosis cases was 1 per 1,000 soldiers. By 1982, only 250,000 cases were reported in the United States. The decline in the number of cases can be attributed to three factors: education about causes of tuberculosis; better diet and nutritional information; and early diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis cases.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

COPD is a term that refers to a group of lung diseases that can interfere with normal breathing. It is estimated that more than 16 million Americans suffer from COPD. It is the fourth leading cause of death in the US.

What are the different types of COPD?

The two most common conditions of COPD are chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Some physicians agree that asthma should be classified as a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, while others do not.

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is cancer that usually starts in the lining of the bronchi, but can also begin in other areas of the respiratory system, including the trachea, bronchioles, or alveoli. It is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women. In 2007, 213,380 new cases of lung cancer are expected, according to the American Cancer Society.

Lung cancers are believed to develop over a period of many years.

Nearly all lung cancers are carcinomas, a cancer that begins in the lining or covering tissues of an organ. The tumor cells of each type of lung cancer grow and spread differently, and each type requires different treatment. More than 95 percent of lung cancers belong to the group called bronchogenic carcinoma.

Lung cancers are generally divided into two types:

- Nonsmall cell lung cancer is more common than small cell lung cancer. The three main kinds of nonsmall cell lung cancer are named for the type of cells in the tumor:

- Squamous cell carcinoma also called epidermoid carcinoma, is the most common type of lung cancer in men. It often begins in the bronchi and usually does not spread as quickly as other types of lung cancer.

- Adenocarcinoma usually begins along the outer edges of the lungs and under the lining of the bronchi. It is the most common type of lung cancer in women and in people who have never smoked.

- Large cell carcinomas are a group of cancers with large, abnormal-looking cells. These tumors usually begin along the outer edges of the lungs.

- Small cell lung cancer sometimes called oat cell cancer because the cancer cells may look like oats when viewed under a microscope, grows rapidly and quickly spreads to other organs.

Would you like to assess your knowledge about Respiratory System? Click here